Separating Signals from Noise

The Whisper

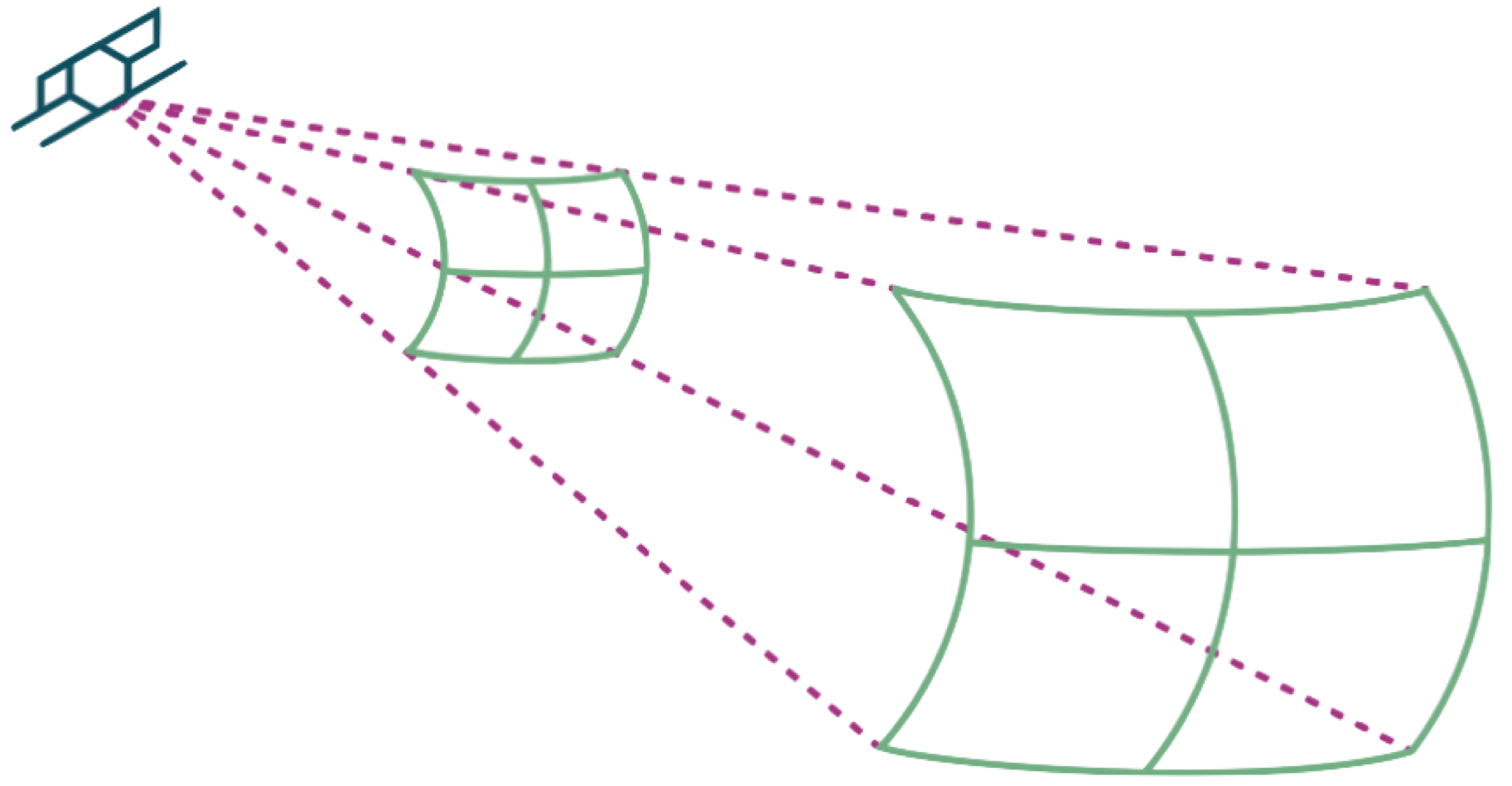

As a radar pulse travels from the antenna to the ground surface its total power remains constant, but as it moves away from the antenna, it spreads out into space and its power density weakens. As shown in Figure 17, it is as if the “skin” of the pulse becomes thinner with distance. This weakening is dramatic; it decreases with the square of the distance from the antenna.

Given that the ground might be 750 km from the antenna, the pulse is quite weak by the time it finally reflects from surface objects. This presents even more of a problem because only a portion of the weakened pulse is reflected toward the receive antenna, and then it has to travel all the way back, weakening again with the square of the distance. By the time the microwaves return to the antenna, they are microscopically faint. The antenna and radar receiver manage to detect, amplify, and record these echoes so that they can be processed into SAR resolution cells that span more than 100,000 brightness values. SAR is amazing.

The Challenge of Noise

Those backscattered microwaves are so weak when they arrive at the antenna that they are perturbed by any noise sources that get mixed in with them. Noise is an artifact of random microwave emissions caused mostly by onboard sensor hardware. One of the tenets of remote sensing is that all objects emit electromagnetic energy based on their temperature. The thermal noise of heated receiver hardware spans wide swaths of the spectrum, including the microwave bands, and this competes with those whispering pulse echoes.

As they struggle to capture those fading backscatter whispers, radar receivers also record random, interfering microwaves that they themselves produce. One of the disappointing aspects of the noise level is that it increases as range bandwidth increases. The large signal bandwidth that the receiver has to be capable of recording also lets more noise enter the receiver.

One of the ways that noise is quantified for SAR sensors is called the Noise Equivalent Sigma Zero (NESZ). This parameter describes the noise floor of an image. All received signals have to be stronger than the NESZ value to rise above the noise level, so it is best for NESZ to be as low as possible. Images with high NESZ values look grainy.

Unfortunately, NESZ is mystifying to SAR users who are not familiar with the dB language of engineering. Many users are confused by NESZ values like -20 dB, which actually indicates a fractional level of 1%. That is, an NESZ of -20 dB means the noise level is 1% as strong as a reference reflection from an idealized metal sphere. An NESZ of -17 dB would means the noise level is 2% as strong as the reference.

System designers have to consider many competing imaging parameters to balance image quality, resolution and noise. For spacecraft, the best choices are increased average power, larger antennas, the use of high-quality receivers with low noise factors, steeper illumination angles, and lower orbits.